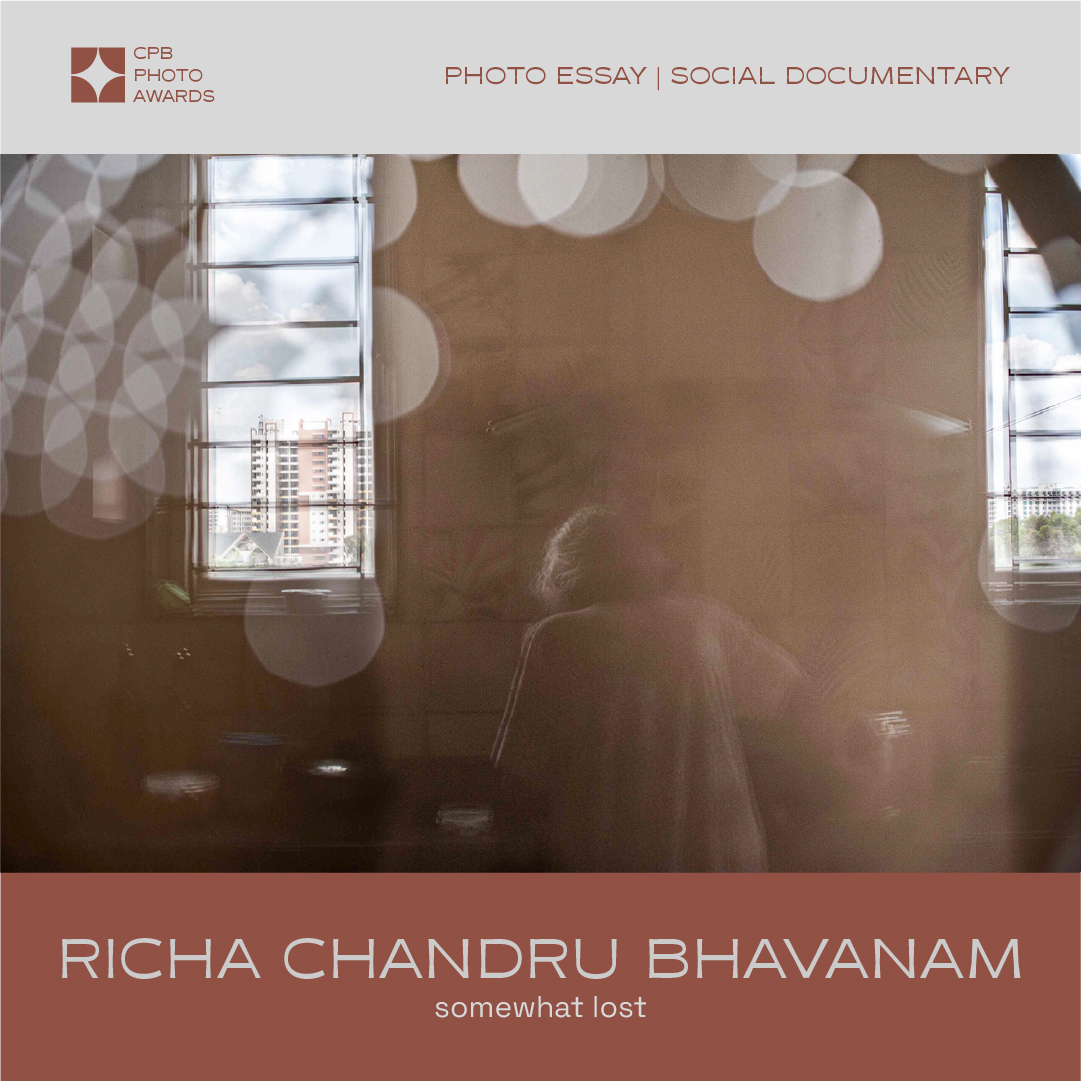

This photo series emerged from a phone conversation with my covid-positive, in-isolation mother:

‘How are you, Amma?’

‘I’m good,’ she said, ‘I just feel… somewhat lost’.

Perhaps it’s this feeling that best describes the experience of living through a pandemic – not just for her but for so many of us.

In my attempt to portray this period in time, I photographed life in lockdown on the near outskirts of Bangalore, where I live with my family – which is bookended by my 86-year-old grandmother and 6-year-old niece. I documented their days as they melted from one to the next, and the world outside as we saw it from our apartment – a world that seems surreal, a world that feels intangible.

Simple acts, like breathing the air around us and touching another person, have become delicate offerings, fragilities that are no longer ours to own. The volatility of these experiences left us disoriented, often yearning for touch and togetherness, and questioning who or what we will find ourselves to be on the other side of this extraordinary time.

Somewhat lost hopes to speak of this experience – the journey through a time of displacement and the longing for a world that belongs to us.

My grandmother in the kitchen

Bangalore, 9th May 2021, 12:39

-1.JPEG)

-1.jpg)